EKPC: Member-owned, but is it member-driven?

Rate payers of rural electric co-ops like EKPC are supposed to have a voice in governance, but lack of co-op outreach leads to poor membership participation

Last fall, Brad Thomas, manager of economic development for East Kentucky Power Cooperative, along with Owen McNeill, judge executive of Mason County, described to a few local residents how they alone had negotiated with a mystery data center developer, what is best for Mason County. Meanwhile, elected officials in town including McNeill, had nearly all signed nondisclosure agreements about the deal.

"It takes 30 or 45 days to get your arms around it," McNeill tells those who've asked for the meeting, in order to have their questions answered. "But this is legitimately a unicorn, and I will say, the best economic development project in the United States, when and if it comes out," McNeill says in the audio shared with The Edge.

"I think that is an accurate statement," Thomas replies.

The population of Mason County has been in decline for decades, something Thomas pointed out to his small audience, noting "You have a dying community." A data center, he continued, "is the type of project that reverses that." It would employ hundreds, he said, while helping to offset property taxes in order to pay for municipal services, among other niceties, went Thomas's pitch. Thomas also tells the group they should be the ones to decide where the hotels will go once the data center is built, attracting visitors.

But hotel allocation is not what the group wants. They want their concerns about noise, about water usage, about the fumes from the probable use of acres of diesel generators while the data center's necessary power infrastructure is built, heard now. They want direct assurances, not a go-between.

"We haven't said no to the data center, but we would be less frustrated with leadership if we'd had a say in all this from the beginning," Max Moran, president of the nonprofit, We Are Mason County, a citizens action group, formed in response to their perception that local elected leaders were keeping the electorate from learning the scope of the deal.

But secrecy is necessary when it comes to data centers, and other industries, an EKPC spokesperson told The Edge.

"Non-disclosure agreements are routine for many economic development prospects," EKPC's Nick Comer said. "For many companies, small and large, a lack of confidentiality will eliminate a site from their consideration. Large-scale data center prospects generally are publicly traded companies operating in highly competitive industries. Disclosures can affect the data center company’s share price, so they take precautions to protect confidentiality until they have made a final decision."

These deals, while often heralding a reversal of fortune for so-called "dying" towns, are still often unpopular in the communities to be impacted, especially since the secrecy makes them wary they will give more than they will get in return. Knowing just how many resources the mystery data center developer will need is not yet fully spelled out for Mason County residents. Thomas says in the audio they can't know until the amount of power the developer plans to use finalized.

"We're negotiating contracts with them as we speak, because it's pre-emptive. You gotta do all that stuff before the project is presented, because if the numbers with us don't work, then this project doesn't work," Thomas explains in the audio.

While it's probably too late for Moran and his fellow concerned citizens to leverage their influence as member-owners of their local EKPC distribution co-op to halt the data center deal if that is what they want, it is not too late for them to start helping their local power co-op to shape policy around how data centers are sited in communities, as well as how to balance the needs of industry with residential customers.

You've got the power

Madison County, like Mason County, is almost exclusively served by an EKPC member co-op. Odds are good, however, that a majority of residents served by these co-ops in each county has no idea about their status as member-owners of their utility, since according to a rural energy nonprofit, more than half of all rate payers enrolled in co-ops are unaware of their membership, and therefore, unaware of their rights as member-owners.

This is because power cooperatives, including the 16 EKPC member distributor co-ops providing power across 89 counties in the state, largely fail to "prioritize member engagement, communication, and accessibility to their full membership," according to the Rural Power Coalition, a national, sustainable energy grassroots organization.

Yet, this lack of communication is contrary to the democratic history of power cooperatives in the US, where all member-owners are supposed to have a direct say about matters of policy, and cooperatives are meant to continually inform member-owners about how their co-op is operating.

"Nothing has changed since the beginning of utility co-ops," Marshall Cherry, president and CEO of Roanoke Cooperative in Northeastern North Carolina, told The Edge. "Every cooperative is driven by the Seven Cooperative Principles, and if you look at Number 5, it says 'education'."

Specifically, the fifth principle states, "Communications about the nature and benefits of cooperatives, particularly with the general public and opinion leaders, help boost cooperative understanding."

Yet, across much of EKPC's coverage area, member-owners often are not informed about their rights to know how and why their co-op is pursuing certain industrial customers, and the impact on communities these large load customers might have.

The birth of RECs

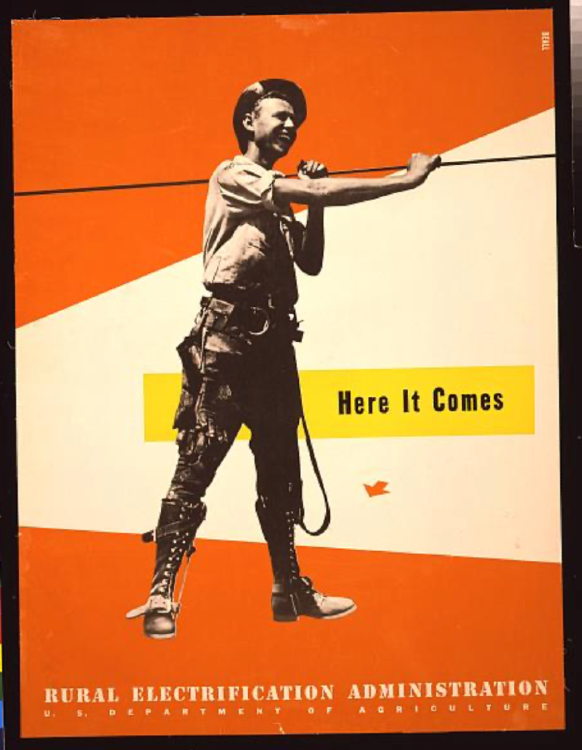

It was in 1941 when 13 East Kentucky power cooperatives banded together to strengthen their ability to meet growing demand for power in their rural areas. Each of the 13 co-ops had been funded and created by local farmers and others who wanted to pay for the infrastructure necessary to deliver power beyond urban areas.

These co-ops, officially known as rural electric cooperatives, or RECs, were being formed across the country at a time when privately owned power companies did not see much point in delivering power to rural areas, as there weren't enough customers to offset the cost of building the necessary infrastructure. So, groups of rural residents would often pool their resources to pay for a line to connect them to the power grid.

To aid them, Congress passed the 1936 Electrification Act, part of President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal. The law not only authorized small loans to fund rural co-ops, it also supported a cooperative governance framework, giving locals the power over their electricity infrastructure. Utility cooperatives have been democratically structured ever since.

The ethos of REC's, according to the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, is founded on a seven-principle code, which spells out how RECs are run via democratic member control, should offer education to member-owners about how they can actively participate in co-op governance, and prioritize community welfare.

Yet, "Many co-ops fail to adequately inform the public about [their membership] and do not educate on the role member-owners can play," the Rural Power Coalition states.

Restructure lacks emphasis on member-owners

In 2010, after EKPC defaulted on creditors, the state Public Service Commission had the co-op audited, finding its "governance standards have not kept pace with current expectations and the board does not meet minimum standards for acceptable governance." The remedy outlined by the PSC was for the now 16 member co-ops to become more involved in how the REC was run, since, the audit read, "the EKPC board seems unwilling to."

Soon after, there was a leadership change and within three years, EKPC was admitted into the nation's largest regional transmission organization, the PJM (Pennsylvania-Jersey-Maryland were the grid's founding states), serving 65 million Americans. It was evidence that EKPC had righted the ship. Additionally, EKPC has earned top bond ratings since 2015.

However, while more fiscally responsible, the corporate restructuring did not seem to emphasize its democratic roots through clear communication with member-owners across the 16 distributor members. The result is that across EKPC's service area, efforts to involve member-owners in governance decisions are inconsistent.

Inconsistent member-owner outreach

Madison County is served by EKPC's Bluegrass Energy, covering 23 counties in Central and Eastern portions of the state. Out of 50 possible points for fair and transparent governance, BGE scored 15 points in a survey of southeastern RECs conducted by the nonprofit Energy Democracy Y'all.

Out of 16 possible points for board meeting transparency, BGE earned a zero. Access to board members could earn a co-op as many as 4 points, but BGE scored just 2 points. Democratic elections at BGE garnered 9 out of a possible 14 points, while financial transparency earned 4 out of 8 points. Overall, when an additional 50 points for member services were added to the scorecard, BGE tallied 43 points out of 100 points overall.

Across the state, the highest rated co-op for governance transparency was North-central Kentucky's Shelby Energy Co-op, Inc., with 25 out of 50 points. Jackson Energy Co-op Corp., with a service area from Irvine to Corbin, rated highest overall with 48 points. Shelby Energy was a close second at 46 points. All of these co-ops are members of EKPC.

When a reporter visited BGE's website in an attempt to find any information about BGE member rights, board meetings, or board elections, the only member-customer rights listed were to do with billing. However, a phone call to the media relations department did quickly result in links for pertinent sites. The list of BGE board directors is here, and the bylaws are here.

"It's not uncommon for member-owners to find that their rural electric co-op does not post board meetings or board elections info on the cooperative's website," Bri Knisley, who directs public power campaigns for Appalachian Voices, told The Edge. "However, it is best practice to make this information transparent and available, in accordance with the cooperative principle of democratic member control," she said.

Not all co-ops are derelict in their duty, according to Kent Chandler, former chair of the PSC. Chandler told The Edge that he is "personally aware of rural electric cooperative corporations conducting giveaways, or allowing drive-through voting to try and spur additional member participation in board elections." Chandler referenced the drive-through voting and give-aways conducted by Farmer's Rural Energy Cooperative Corp., an EKPC member in South-central Kentucky. Farmers scored 43 out of 50 in the survey.

In other parts of Appalachia, there is an obvious emphasis on member-owner participation. The Powell Valley Electric Coop in New Tazewell, Tenn., for example, issues a guide book to member-owners, instructing them on how to participate in governance. The Roanoke Cooperative in North Carolina, has a page on its website dedicated to member-owner activism, and another page that invites members to ask for board information, including meetings and votes.

"We have yearly town hall meetings, and other forums to ensure our members are able to participate and are informed," Roanoke CEO Cherry said in the interview.

A note on semantics: EKPC uses the phrase "member-owners" to refer to its 16 distribution co-op members. That is not the universal usage of the phrase, according to Tom Llewellyn, communications director for the Rural Power Coalition. “'Member-owners' are generally understood as being those who are paying power bills to an electric co-op," he said. At EKPC, rate payers are referred to as "consumer-members".

'Just trust us'

The local EKPC member co-op in Mason County is Fleming-Mason Energy Co-op, Inc.; it scored an 11 out of 50 points for governance transparency in the Energy Democracy survey. Lack of communication between Fleming-Mason and Mason County member-owners helped set the ground for mistrust between EKPC and some citizens in Mason County.

"I had not known that as a customer of Fleming-Mason, I had any rights to have a say in its governance," Moran told The Edge. This failure on behalf of his local co-op, Moran said, diminishes his faith that EKPC's Thomas, or anyone involved in negotiating the deal, will be forthcoming about potential adverse impacts of a data center on the community.

"The way it is now, the guy from EKPC [Thomas] and the judge executive are basically just saying, 'Trust us,'" Moran said, noting the irony of how elected officials must keep secrets from the people who elected them in order to serve the interests of an outside developer. "They say it will benefit us, but how do we know that?"

That Thomas is representing members of Fleming-Mason Energy Cooperative in a data center deal is both right and wrong, according to experts. It's correct that a cooperative the size of EKPC should have someone knowledgeable to help meet the needs of data center developers while also protecting member-owners from elevated rates, according to Cherry, who is unfamiliar with the specifics of the data center deal. But, that those same rate payers were unaware there was even an economic development staff member suggests they are vulnerable, says another.

"If you are a member-owner and you don't know how your co-op is run, then you don't know who is negotiating on your behalf, and whether they are making your needs and wants known," Chris Woolery, energy projects coordinator for Mountain Association in Berea, told The Edge.

New load tariff

Data centers could be good opportunities for both rate payers and their power cooperative, according to Cherry. "Large load customers can help make a utility run more efficiently, and offer the opportunity to sell a lot of power which can help keep rates low for everybody else, but there are a lot of complexities with a data center," he said.

According to a federal report, data centers are driving up residential rates by an average of 7.4%, especially when powered by investor owned utilities that are not bound to return profits to its member-owners, as rural power co-operatives are.

In the audio, Thomas claims that EKPC has mandated the mystery developer pay for every scrap of infrastructure necessary to service the data center. "We're not giving them some sweetheart deal and begging them to come. They are not going to have the lowest rate on our system by any means. The value for them is we provide them reliability," Thomas says in the audio.

Last October, the PSC approved a large load tariff (rate and terms) submitted by EKPC. The document stipulates large load customers such as data centers and other industries requiring 15 megawatts or more, pay all the costs associated with their power generation needs. Industrial customers requiring more than 250 MW are required to "provide a power supply plan with a dedicated resource in order to minimize risk to other members."

How this will look in practice is still unknown.

"It says that new load customers will have to pay their way, but it does not explain how," Woolery said. "We can be cautiously optimistic that they are protecting the rate payers. Why would they want to do otherwise?"

Coal or what?

Something Thomas did not mention in his conversation with the Mason County citizens is that EKPC owes over a billion dollars to the federal government for loans taken to improve infrastructure across the 16 distribution cooperatives. Because power co-ops are not allowed to profit, nor are they eligible for certain federal subsidies given to for-profit utilities to help keep the nation's grid operable, a large load customer such as a data center could mean selling enough power for EKPC to significantly reinvest in its infrastructure.

But will those investments be in antiquated fossil fuel technology or in newer—and cheaper—sustainable energy sources? EKPC's current plan is to keep the Spurlock and Cooper coal-fired plants operative, retrofitting them to be interchangeable with natural gas. This is not the only option, however, according to the Rural Power Coalition, and Woolery.

"I tell you that the whole state is at a crossroads, and every new generation investment is a 40 year commitment," Woolery said. He added that member-owners need to be more involved in their respective co-ops, "telling the decision makers that we can meet all our needs, both the need for extra power for data centers, as well as our needs at home, by investing in low risk technologies for energy efficiency, conservation, and load control. That way our bills will be lower, and then, even if the data centers don't come, in the worst case scenario, we will have made the right investments that lowered our bills."

Power to the people

The first step to flexing your power as a member-owner is to track whether your monthly electric bill is trending upward, according to the Coalition. The possible reasons for higher bills are many, ranging from drafty and energy-inefficient buildings to a badly-maintained grid, and everything in between. Tracking your electric bill gives you data and something to ask questions and focus on what could be improved.

Next is to gather the bylaws, board of directors information, and meeting protocols for the co-op board which is typically on the co-op website, if it's listed at all. What follows from that depends on what you and fellow member-owners would like to tackle first. The Coalition has a toolkit to help you start "voting

in the board elections, advocating for different energy policy, or simply just

spreading the word to family and friends," the toolkit says.

Next for Mason County

Moran and other members of the citizen action group, fear it is too late in the process for their concerns to be addressed, although there is still a fiscal court vote yet to happen on whether to create an ordinance that will change the requisite data center zoning from agriculture to industrial.

"But we think it's already a done deal," Moran said.

While the Mason County elected leaders' secrecy about the data center project points to flaws in our state's current system of economic development where residents of shrinking communities must put blind faith in leaders who say they are committed to what is best for all, how those deals are led by EKPC remains a way Kentuckians can shape by getting involved in their co-op governance.

"If members are interested in more transparency in board undertakings, they are welcome to elect members committed to providing as much," Chandler, the former PSC chair, said.

Sign up for The Edge, our free email newsletter.

Get the latest stories right in your inbox.