Coal country: too costly for factories, just right for data centers

Kentucky's lost smelter opportunity shows how reliance on fossil fuel repels new jobs, attracts big servers and secret deals in the high tech race to be the biggest AI company. Is Madison County ready for Meta and more?

This is a special land use report from The Edge

Land use reporting at The Edge is made possible in part by a grant from The Listening Post, and a gift from Richard and Cheyenne Olson, and from Sune Frederiksen.

This week, Century Aluminum announced it will build a new smelting plant—the first such smelter to be constructed Stateside in nearly half a century—in Oklahoma. The plant is expected to bring over 1,000 permanent jobs to Inola, the town where it will be built. The reason those jobs won't go to Kentuckians, according to experts, is that industrial energy in Kentucky has grown too expensive.

"We waited too long to build out our clean energy," Lane Boldman, director of the Kentucky Conservation Committee, told The Edge in an interview. "We've got an aging fleet of coal-fired power plants, an aging grid, and we need projects to help with the investments," Boldman said.

For a time, Century was considering a site in Northeastern Kentucky, as Governor Andy Beshear's office announced with fanfare in 2024. But with the manufacturer's half billion dollars in federal Investment Recovery Act money to be spent exclusively on green energy, Kentucky's chances were hobbled.

But bringing in those big projects is increasingly more difficult as our industry energy costs continue to climb. "If companies have sustainability goals, there is not an easy mechanism for them to come here," Chris Woolery, energy projects coordinator at Mountain Association told The Edge in an interview. "They could engage with the state and the utility to create a special contract, but they don't have time for that."

The cost of energy per kilowatt in Kentucky and Oklahoma are about the same—about .12 per hour. However, 60% of Oklahoma's energy comes from renewable sources, whereas less than 10% of Kentucky's does. "To be fair, Century wanted really cheap energy, three cents per kilowatt," Boldman said. That Oklahoma already has more sustainable energy infrastructure means that it will be less expensive to accommodate that low energy price.

"We haven't made enough investments in solar storage and transmission," Boldman said.

Antiquated policies

Kentucky has gone from being the cheapest energy producer nationally to the 12th cheapest over the past quarter century. By relying less on coal and investing more in renewables, a new report found Kentuckians could pay nearly $3 billion less in energy costs over the over the next 25 years.

The report, commissioned by the Kentucky Resources Council, Earthjustice, and the Mountain Association, said that coal accounted for only 15% of all US energy production in 2024, but according to federal data, 67% of Kentucky's power was coal fired. Yet our legislators continue to insist on coal first through the formation of the Energy Planning and Inventory Commission (SB 349) whose job it is to find ways of reducing energy costs while at the same time, putting coal first.

The General Assembly has also made provisions for data center companies to receive tax breaks for equipment purchased.

Meanwhile, all four Kentucky power providers, East Kentucky Power Cooperative, Kentucky Utilities, Louisville Gas & Electric, and Kentucky Power, are all seeking to maintain their coal-fired operations while asking for rate increases, anywhere from $5 per month for EKPC members to $27 for KP customers.

Now, instead of welcoming home a familiar industry—Northeast Kentucky was once Century's largest US smelter, but the company cites high natural gas prices after the eruption of the Ukraine War for closing the site—with its plethora of jobs and lack of mystery about what is expected from the community in return, the region is feeling its way into being neighbors with a secretive data center. The mystery company will employ a mystery number of locals in exchange for about 8,000 acres of farmland near the Ohio River, purchased by developers who required local elected officials and others to subvert the democratic process by signing nondisclosure agreements. The developer will not be revealed until just before breaking ground.

Such conundrums are increasing across mostly rural Kentucky communities, thanks to the combination of regressive state energy policies and the outsized influence uber-wealthy data center operators have versus the ambivalence of farmers and others who value their rural way of life but aren't sure how to protect it in the face of economic analysts who say, "Grow or die."

In Madison County, where planning and zoning officials in all three jurisdictions told The Edge that data center policies have yet to be formulated, as thousands of acres of farmland are being converted into industrial parks, what potential crises might be waiting around the corner?

Cloak and dagger

Secrecy used by dealmakers who wish to keep their competitive edge around industrial deals is nothing new, even if it is controversial. But when nondisclosures and back room deals force elected and other municipal authorities to place the interests of companies above those of their constituents, trust is broken and community relations become fractious.

In Oldham County last year, the judge executive fired his deputy judge executive citing a "loss of faith" after it was revealed that the deputy had surreptitiously recorded a private meeting between his boss and data center developers seeking to locate in the County amidst public pushback over the deal. The deputy, Joe Ender is now suing for wrongful termination and violation of the Kentucky Whistle Blower's Act.

That case has slowed however, because not long after he filed suit, he was indicted by the state attorney general's office for allegedly using Oldham County road department equipment on his private property. The Oldham Era reports that Judge Executive David Voegele claims he had nothing to do with Enders' indictment. In a hearing earlier this month, Ender denied the charges.

Kentucky is a "one-party consent" state, meaning it is legal for one party of a conversation to record without the other party's or parties' explicit permission. For now, a moratorium has been placed on data center billing in Oldham County.

'Owning local officials'

"That deputy judge executive was looking out for their people," Mason County resident Max Moran told The Edge in an interview. "He has [Oldham County officials] on a hot mic saying to the developers, 'Whatever you need, we'll take care of it.'"

These kinds of non disclosed dealings are common, according to a study. The authors found that 25 out of 31 data centers studied had negotiated behind the cloak of secrecy, avoiding any public discussion of the respective developer's plans. "[T]he widespread use of non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) and a larger ethic of secrecy regarding data-center development curtails this discussion and, in so doing, impairs local democracy," the authors wrote.

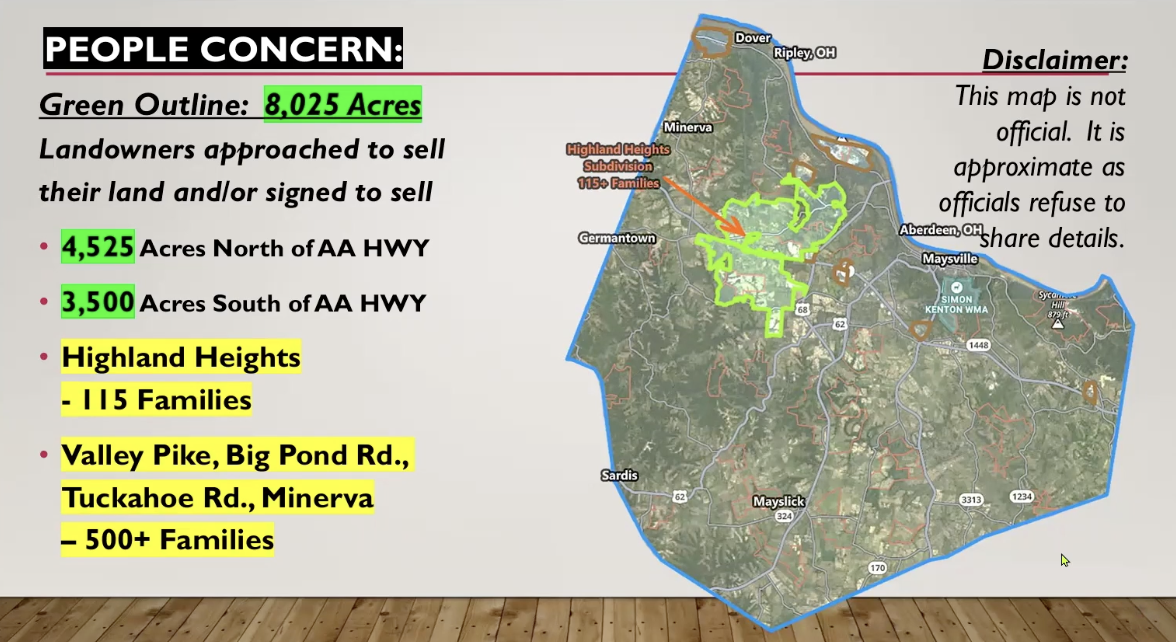

Moran, an aerospace engineer who also runs a family cattle farm, is president of We Are Mason County, a nonprofit organization he and other County residents formed to oppose their elected officials' secret handling of a coming 2.2 gigawatt data center. Estimates on how many homes 1GW of energy can power for an entire year range from 750,000 to 900,000. The Mason County data center is rumored to include a massive military artificial intelligence center as part of a "coheadquarters" for a top artificial intelligence company.

The nonprofit, said Moran, got started, "From just people talking about how they'd been approached about their land, then being told to sign an NDA. It made them suspicious," Moran said in the interview, noting that farmers in the Ohio River border county have fielded inquiries from the developer on over 8,000 acres of productive farm land.

The group began working with Boldman to help navigate policy and other decisions around the data center, after they approached elected officials about the land deals, and discovered their leaders were already "owned" by the developers.

"We think they signed NDAs probably in 2024. When the land deals began in the summer of 2025, the Public Service Commission approval process was already underway, having initiated in early 2025. The tariff (the terms and conditions for energy delivery) created for the developer by EKPC, which is helping to land the deal, was blessed by the PSC, and is now in place. The name of the developer is redacted from all documents throughout.

Moran said his group is not outright opposed to the data center, and do not wish to tell land owners what to do, especially since the offers of up to $60,000 per acre could create generational wealth. What they do oppose is the lack of transparency and community input. "It's about protecting those people who don't want to sell and the people who are going to have to look at the stupid thing," he said.

Land hungry

In what has become the half a trillion dollar industry of creating artificial intelligence with large language models, data center developers like Meta, Amazon AWS, Microsoft, and others such as the Stargate collaborators OpenAI, Oracle, and SoftBank, are more than willing to pay Kentucky's rising industrial energy costs, because of our relative abundance of inexpensive and undeveloped land, according to Boldman.

"They just want to line up all of the components and make a deal," she said.

Certain areas are more desirable than others to these tech titans, however. In Mason County, that it is home to EKPC's Spurlock coal-fired power plant means the data center developer can connect that much more easily into the PJM grid, County officials have claimed.

The PJM is the world's largest power network, and includes 13 states in the Northeast, MidAtlantic, and Midwest regions of the US. But for Spurlock to mange 2.2 GW, it would need to be upgraded first, something Mason County officials say their mystery company will cover.

"The expansion will have to happen to the get the power they need," Moran said.

Thirsty servers

Beyond being shrouded in secrecy, common complaints about data centers include that they suck up a tremendous amount of resources, including thousands of acres of land in perpetuity and millions of gallons of water per day. Typically, data centers use water to cool their servers that become heated from all the artificial intelligence grinding, although novel water saving technology could be used in data centers yet to be built.

The new cooling systems allow data centers to have a one-time use of the requisite amount of water (typically a million gallons or more) that they then recycle through a closed-loop cooling system. This is the type of cooling that Stargate's Abilene, Tex., 1.5 GW campus uses.

Data centers that are air cooled use less water but destroy a community's peace and quiet as the sound of their cooling equipment can be heard humming even miles away.

Still, even if a data center is built to use less water, unless the developer also builds its own power plant, it's likely that an enormous amount of water will be used by the power plant that feeds the data center. In 2024, Shaolei Ren, a University of California, Riverside professor who studies data center water usage, told Grist that power plant water consumption "can be as much as three to 10 times as large as the on-site water consumption at a data center."

Rate increases

The most insidious of all adverse effects of data centers is how, on account of the enormous amount of power they require, the cost of providing that energy typically falls to rate payers, often without any explanation for why the rates rise. That's because not only do data centers force power plants to use more water, they also require utility providers to upgrade infrastructure.

For-profit utilities such as KU and LG&E are rewarded by the federal government with the right to profit off of any upgrades made to their infrastructure. When they improve their energy delivery in order to meet the huge demands of data centers, they then pass along the costs plus a little extra to other rate payers, including residential ones.

For the average customer whose rates increase, a Harvard Law School study found that state public utility watchdogs like the PSC in Kentucky, make it more difficult to discover the reason why rates spike because of all the confidentiality granted to data centers in the approval process. The clandestine process also makes it more difficult to determine whether the charges are reasonable in relation to the actual cost of the upgrades.

Nonprofit member-owner rural electric cooperatives such as EKPC's 16 member utilities, must rely on the developers of large projects such as the Mason County data center to help pay to upgrade their facilities. That's because REC rates are not subject to the same federal regulations, nor are they eligible for certain federal grants that could help cover the cost of improving infrastructure. Instead, they were designed to be democratically operated by their member-owners, with the expectation that they will deliver energy at the lowest rate possible rather than at a profit. The downside is that without large projects, it's more difficult to upgrade the infrastructure to include lower-cost green energy, keeping the co-op tied to higher cost, aging infrastructure.

Mushy jobs claims

Stand Together, funded by Charles Koch, claims that data center jobs are retooling how we think about jobs and education, and suggests new programs aimed at educating non-degree holding employees will allow them to prosper as never before in data center that hire up to 150 people, a far cry from 1,000 factory jobs.

Typically, data centers are so automated, very few personnel are needed. For the Stargate campus in Abilene, there are about 350 employees in a campus that is over 1,000 acres big, suggesting data centers might occupy large footprints in their communities, while not really contributing much in the way of economic activity.

In Mason County, those who signed the NDAs say the company is telling them there will be 400 permanent jobs after all the construction is over. But there is no way to prove this, Boldman points out.

"It may not be the best situation for everyone in the long run," Boldman said. "People are trying to make a strategic decision without all the facts. There is no way to know whether what is in a proposal is what will end up being what happens."

Stand Together, along with its sister organization, the Koch-funded, Americans for Prosperity, are cross branding their pro-data center message. Meanwhile, the Madison County chapter of the Republican Party has agreed to let Americans for Prosperity help run their election events this year.

Boldman said there is also the concern that the half-trillion dollar data center boom is headed for a fall. "There may be a burst bubble coming. People are taking risks before they maybe are fully aware of the consequences," Boldman said.

Duncannon Lane could fit a data center

Of all the many acres bought up and zoned for industry anywhere in the County over the past two decades, Richmond has the most notable. The stretch of 1,500 contiguous acres of farmland (the Begley Property plus the 600 acres optioned from them by the City of Richmond) along Duncannon Lane in the southern annexed portion of the City, is large enough to host a data center. It also has access to EKPC substations. Whether it could be upgraded by EKPC to meet high load demand of some capacity, would depend on how much a developer would be willing to invest.

In 2023, EKPC testified to the PSC that they have had queries from customers interested in locating in the Duncannon Lane area, seeking as much as 420 Megawatts—nearly half a gigawatt—of power within 18-24 months.

There are also the 800 acres near the Kentucky River recently purchased by the Madison County Fiscal Court, the approximately 300 acres set aside in Berea for the regional business park, and several other smaller industrial sites within the County limits.

"Sure, Madison County could see a data center, but it has to have all the resources, land, the ability to handle high transmission," Boldman said. "But the question is what is the best use of your resources? is it going to be a business that largely is construction jobs only and not a lot of long terms jobs or is tis a business that can sustain an economic base for a long time, including jobs for constituents."

'Caught off guard'

Earlier this week in Simpson County, data center developer TenKey LandCo, LLC, sued the town of Franklin for imposing restrictions on data centers before the developer could have its plans for the 200,000 square foot site on 200 acres, approved. TenKey is arguing that the move is illegal.

Communities such as Franklin are being "caught off guard", Boldman said. "These data centers are just popping up all over the place, and communities aren't ready for them. But there is good material on best practices coming out from different sources based on the communities that have already been hit," she said. The KRC recently released its Data Center Ordinance Model Guidance which is designed to, "address the lack of readily available tools to guide revisions to local land use planning and zoning ordinances and to help localities regulate the siting of large data centers and their operation within their communities."

Madison County Deputy Judge Executive Jill Williams said that to date, the County neither has any planning and zoning guidelines specifically for data centers, nor has any application been made to build one within the County's jurisdiction. "It's definitely not something we're recruiting," she told The Edge.

Berea also does not have zoning in place, nor any applications for data centers on file, according to Melissa Isaacs in the Planning and Codes department there.

Richmond's city planner, Kevin Causey, told The Edge that currently, there are no data center-specific guidelines in the City, but that its Industrial Development Corporation will be setting some guidelines for what kinds of industry Richmond wishes to attract once the new executive director is installed next month.

Boldman cautioned, "Before people invest in these kinds of projects, do not be swayed by the hype, because they are only proposals, but in the mean time, the utilities may make investments beyond what is really necessary."

Comments, questions? editor@theedgebereaky.com

Sign up for The Edge, our free email newsletter.

Get the latest stories right in your inbox.