What in the world?

As number of US embassy posts filled globally hits historic low, number of presidential appointees overseas is unprecedented

In December, the US government quietly dismissed 30 career diplomats serving as ambassadors around the world. The move drew little public attention, but its consequences could be significant. Combined with existing vacancies, these dismissals mean that 44% of US ambassadorial posts are now unfilled, leaving many missions abroad without permanent leadership at a time of global instability.

Presidents have long replaced ambassadors appointed by their predecessors. That practice is neither unusual nor controversial. What is different today is the scale of the vacancies and what they reveal about a deeper question: whom do ambassadors actually serve? Are they meant to be professional representatives of the United States, or personal envoys of the president?

Ambassadors in the US fall into two broad categories. Some are career Foreign Service officers who have spent decades learning languages, managing embassies, and navigating complex political environments. Others are political appointees, trusted confidants of the president. Both types bring advantages. Career diplomats offer institutional memory, technical expertise, and credibility with foreign governments. Political appointees, by contrast, often enjoy direct access to the president and the authority to advance the administration’s agenda quickly.

Supporters of political appointments argue that loyalty matters. Career diplomats can be cautious and risk-averse, focused on continuity rather than innovation. Political appointees may be better positioned to push bold initiatives and deliver clear messages aligned with presidential priorities. They also give presidents greater control over foreign policy execution.

But there are costs. Removing experienced professionals can weaken U.S. credibility abroad, particularly when foreign governments see embassies led by inexperienced figures or left vacant altogether. Diplomacy depends on trust and continuity. When ambassadorial posts remain vacant, US reliability is called into question.

Management also matters. Career diplomats typically rise through the ranks and are better equipped to run large, complex embassies. They are often more respected by embassy staff and more willing to serve in difficult or dangerous postings. Political appointees, by contrast, tend to favor prestigious assignments and avoid hardship posts, leaving career professionals to fill the gaps.

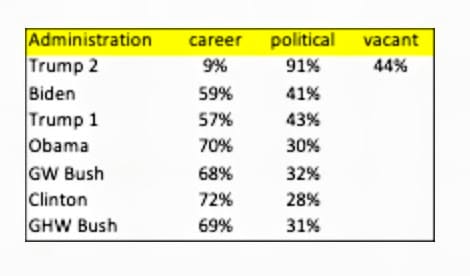

Data from the Department of State suggest that this shift toward political loyalty over professional experience is not accidental (see table below). In the first year of the second Trump administration, 44% of ambassadorial positions remain vacant. Of those filled, President Trump has appointed 70 ambassadors, compared with 45 appointed by President Biden. Only 9% of Trump’s appointees are career diplomats, the lowest figure since 1988, while 91% are political appointees, the highest on record. This is unlikely to be a coincidence.

These numbers align with the administration’s governing blueprint, The Mandate for Leadership, also known as Project 2025. The document clearly states that since “personnel is policy, ” the second Trump administration “should both accept the resignations of all political ambassadors and quickly review and reassess all career ambassadors… [where] priority should be to put in place new ambassadors who support the President’s agenda among political appointees, foreign service officers, and civil service personnel…[and] Political ambassadors with strong personal relationships with the President should be prioritized…”. The message is clear: loyalty comes first.

Every administration has the right to appoint officials who will carry out its policies. But modern diplomacy is complex, technical, and long-term by nature. It requires experience, institutional knowledge, and an understanding that national interests extend beyond any single presidency. When ambassadorial appointments are driven primarily by personal loyalty rather than professional competence, they tend to serve short-term political goals rather than enduring national interests.

Why should this matter to Kentuckians? Because foreign policy is not an abstraction. Kentucky’s economy depends heavily on international trade, and its interests are represented by US embassies across the globe. Many Kentuckians also serve in the State Department and the Department of Defense and are directly affected by leadership gaps overseas.

Kentuckians saw how during Covid-19, Senator Rand Paul (R-Ky) leveraged his power as a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which confirms ambassadorial appointments. During the Biden administration, Paul temporarily stalled all ambassadorial appointments, in order to force the administration to honor his request for information on the origins of Covid-19.

The question, then, is not merely whom ambassadors serve. It is whose interests are being represented abroad, the nation’s or a president’s. That answer ultimately depends on whether the public demands professionalism, continuity, and credibility in US diplomacy, or accepts a system driven by personal loyalty and political reward.

Jose E. Mora, PhD, is a former Professor and Chair of Global Affairs of the American University of Phnom Penh in Cambodia. Mora and his wife, Melissa, recently moved to Berea in order to be closer to their four adult children who also live here