Region's system for feeding the hungry being sorely tested

Spike in demand for food hits charities across the edge of Kentucky's Appalachia

Karen Linville has been helping to feed the hungry for two decades now. In all those years, this is the most desperate time she's seen for folks who rely on the Berea Baptist Food Bank, which she helps to operate just around the corner from the church, on Parkway Street.

"We would usually serve anywhere from 50 to 75 families by the end of the week," Linville said. "Sometimes we'd have 20 families each time, but that's doubled now. On Monday, we had 40."

The Berea Baptist Food Bank is open four hours a week, two hours on Mondays, and two on Fridays. Linville said the majority of the food bank's clients are families and seniors who have been coming to the food bank for a long time.

"It's just getting worse," Linville told The Edge in an interview. "They had their benefits cut off last week, but it's been getting worse for some time. We've been seeing this for a while."

Hungrier than ever

Current political warring in Washington notwithstanding, national data support Linville's observation that hunger was trending upward, long before the government shutdown. Federal data from 2022 through 2023 show that hunger ticked up from 12.8% to 13.5% during that time. Or, put another way, two years ago, there were 18 million hungry households in the US.

Other federal data suggest these numbers have remained high. Spending last year on assistance programs such as SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), totaled almost a 100 billion dollars ($99.8bn), with each of the program's 41.7 million beneficiaries receiving an average $187 per participant each month. That's according to the USDA (US Dept. of Agriculture), which administers federal nutrition programs. Nearly 42 million recipients of SNAP is well over 12% of the population. SNAP is only about three-quarters of all federal nutritional assistance spending.

With that level of reliance upon federal nutritional help, a disruption in the system such as this administration's lack of clarity on whether and when SNAP benefits will be distributed, can throw food banks into chaos.

As of November 1st, all SNAP benefits were curtailed by the Trump administration indefinitely. Earlier today, however, the USDA released a statement saying it will comply with a recent Rhode Island judge's ruling that all SNAP benefits must be released today. Trump blames the Democrats for his decision, and is appealing the decision. Meanwhile, several other states, including Kentucky, are also suing the administration in a Massachusetts court over harms caused by witholding SNAP.

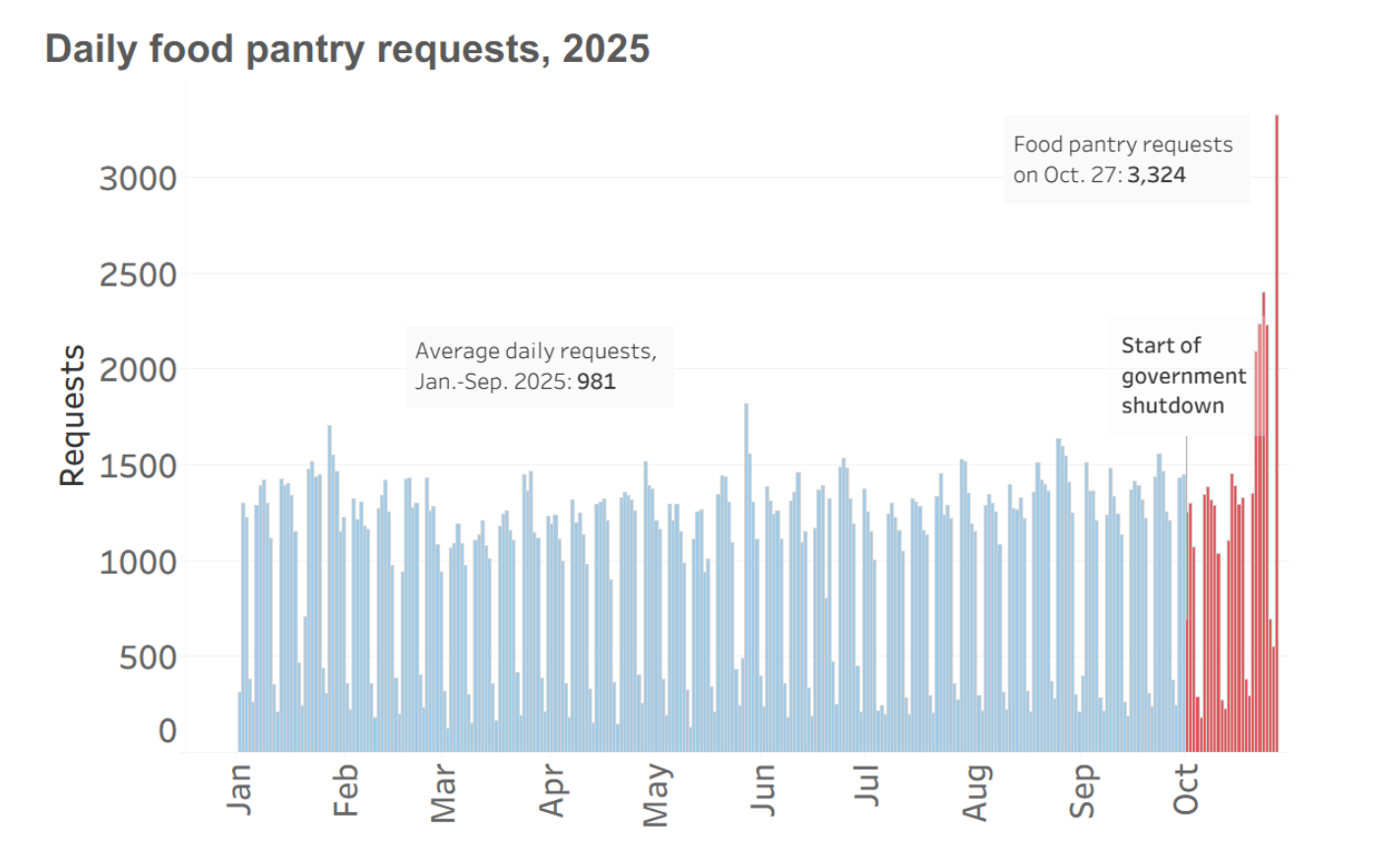

A report released last week by Washington University in St. Louis, Mo., found that calls to 211 food bank hotlines nationally had doubled, even before the Trump administration paused SNAP payments on November 1st. "After holding steady at an average of 981 requests per day from January through September, the number of requests for help finding food skyrocketed on October 27 to 3,324," the report reads.

Closer to home, Laura Brooks, communications director for God's Pantry in Lexington, said 250,000 people in 50 central Kentucky counties rely on the distribution of $40 million in federal assistance monthly. Without SNAP, there is an increased threat of hunger.

"For every one meal we provide, SNAP provides nine," Brooks told The Edge in an interview. "And that is money they are putting back into the community, including with local farmers, too," she said. SNAP benefits are placed on a debit card that can be used at most food retailers, including farmers markets.

Food banks need money not food

The Berea Food Bank sits about a block away from the one Linville helps to run on Parkway Street. Its director, Tony Crachiolo, told The Edge his establishment no longer accepts any food donations.

"About 25% of the food would have to be thrown away because it was expired or damaged in some way, and then the volunteers would have to sort it, and it had to be weighed for tax purposes," Crachiolo said in an interview. "It was a very labor-intensive process."

Now, the Berea Food Bank leverages donated funds to buy in bulk from God's Pantry in Lexington––Berea Food Bank's primary supplier––or from other retailers, in order to meet the needs of its clientele, which he said includes many families, seniors, and others.

"We can do oh so much more with a ten dollar bill than the average person can," Crachiolo said. "For example, we can buy 24 boxes of mac and cheese, a food pantry staple, for $8.80 right now. And that would feed four people. So, four times 24 for essentially eight dollars. But if you were to use your $8.80, maybe you'd be able to buy five boxes."

Crachiolo said making the shift to accepting money not only has greatly increased Berea Food Bank's capacity to feed people in need, but has also allowed it to have a "meal-centric, balanced inventory."

"Our inventory is designed to provide a healthy, nutritious diet. We don't have a lot of processed foods," Crachiolo said. "We used to have to provide a mishmash of things that didn't necessarily go together, but was what we had in donations."

Working with a nutritionist, Crachiolo said the Berea Food Bank now offers its clients "whole grains, fresh and canned fruits and vegetables, dried fruit, nuts, dairy products, and lean meats. We also have beans, rice, spaghetti, spaghetti sauce, tuna, and Tuna Helper. Self stable milk. Cereal. It's 21 meals for each individual. A week's worth of groceries to a family."

For food pantries (pantries are run more like a small grocery store, where guests can choose their items) run by the Christian Appalachian Project, including in Jackson and Rockcastle counties, money also goes further than food donations, according to Tina Bryson, that organization's communications director.

"We'll accept food, but money is better because we can be more flexible. We can see what is needed most in the moment," Bryson told The Edge. "Maybe we really have a demand for baby food one day and staples like rice or potatoes the next."

The Christian Appalachian Project runs food pantries in Jackson, Rockcastle, Magoffin, and McCreary counties.

Money, and in particular, more of it, also helps food banks meet the rising cost of food. Linville said that since September, and especially last month, the cost of food for the people the Berea Baptist Food Bank serves has increased significantly. "The truck comes twice a month, and it usually runs about $1,000 each time, so about $2,000 each month, but last month w spent over $3,000," she said. "But it could be up to $4,000, some times, too.

Food supply chain

The top of the food supply chain for the food bank network is an advocacy organization called Feeding America, which has offices in all 50 states. Feeding Kentucky, one of the parent office's affiliates, helps not only advocate for legislation that helps reduce hunger, it also helps find suppliers and other support for places like God's Pantry in Kentucky.

Once God's Pantry is supplied, it then supplies regional food banks. The local food banks in turn serve their specific community. It's not unheard of for a person in need to end up at a food bank outside of their own community, however.

"We won't turn them away, but what we'd rather do is provide them with a list of resources nearer to them so they don't also have to be hit with the additional financial hardship of paying for gas to drive farther than they have to," Bryson said.

Like the local food banks, God's Pantry accepts money, but as the main supplier for virtually all food banks in Central Kentucky, its main focus is securing enough food to supply the local food banks. Brooks said that a third of her organization's food inventory comes directly from the USDA, and that until recently, much of the rest of the food they distribute came from food manufacturers.

During the current federal government shutdown, the USDA has continued to ship food to God's Pantry, Brooks said, but manufacturers have been sending next to nothing for a while. "They've been trying to avoid waste, and have been getting more efficient to keep their costs down, so they don't really have anything to give us any more," she said.

Governor Andy Beshear recently released $5 million to Feeding Kentucky from the state's so-called "rainy day fund". The organization released the money to SNAP beneficiaries on November 4th, but it will not cover the entire month's need.

'Ask fatigue'

Bryson said the number of new families now coming to the food pantries run by Christian Appalachian Project is at least 50 per month, per facility, and sometimes much higher.

"[Our] coordinator at the Grateful Bread Food Pantry in Mt. Vernon, said normally they average about 50 families per day," Bryson told The Edge. "Sometimes it's as high as 75, normally. But this week, they have seen as high as 112 families served in a day."

Bryson also said that many of the families who visit the pantries are regular customers that are now coming more often. "Other people who used to come but then got back on their feet, they're coming back now, too," Bryson said. "We also have a lot of federal employees who work at the prison in McCreary County. We've never seen that before."

Brooks from God's Pantry said that the demand for food from new households across all of the food banks God's Pantry serves in Central Kentucky spiked 37% between October 1st and November 1st.

To meet this increased demand, Brooks said her organization has turned up the burners. "We are asking our community to step up. We are actively fundraising. We are asking people to contribute their time, whether it's as a volunteer or by advocating. We're asking people to donate because for every one dollar donated to us, we can create six meals."

But, Brooks said, no matter how much nonprofits seeking to help feed the hungry step up their efforts, "there is always 'ask fatigue'," where donors say they just can't do anymore.

All organizations interviewed for this piece agreed that there is always the threat of running out of resources, but that for now they are all keeping pace, finding support from their communities and learning where to ask for more.

In Berea where the City has donated and rehabilitated the house where the Food Bank is located, and where it covers the cost of the organization's utilities Crachiolo said, "We are incredibly grateful to the City. There are very few cities who step up in this way, and they have done so for the past 20 years."

If you'd like to donate to a food bank, now is a good time, as many are currently running fundraises where all donations are matched dollar for dollar.

Berea Baptist Food Bank: 859-986-9391

Berea Food Bank: 859-985-1903 Facebook page

Christian Appalachian Project: website

God's Pantry: website

Update: The Edge regrets spelling Mr. Crachiolo's name incorrectly. It has been corrected.

This Monday through Friday, I spent my days and evenings going to meetings, interviewing people, fact checking, and researching hunger and how to beat it. And that was all before I even started writing. In all, it was 23 hours of my life dedicated to the stories in The Edge this week.

Good reporting takes time. And time is money. If The Edge is something you rely on every week to stay informed about your community, then please considering contributing your financial support. It means a lot.

Thank you